What makes a Happy City?

I felt sad when I finished reading “Happy City” the other day. Vancouver author Charles Montgomery weaves together stories, interviews, culture and information in such a compelling way that I felt like a month-long conversation had ended. When I began reading it, I gushed about it on Facebook and with good reason. It has something for any city dweller — from the history and science of happiness and behaviour, to impacts of transportation on wellbeing, to dwelling types influencing social interaction. I returned it to the library reluctantly after my initial 14-day restricted loan period was up, and waited anxiously to get it back until another copy was returned six days late. (I guess the other person liked it even more than I did.) I felt its absence like a close friend.

Probably the truth that hit me most is how messed up American cities are, structurally. Sure, we have sprawl here (I’ve lived in it), and apparently Vancouver has the worst, or second-worst, congestion in North America, but places like Atlanta have for decades sought an American dream that is now turning into a nightmare. These car-centric “communities” have large houses spread farther apart on larger lots than we do, of which I wasn’t aware, and this causes a host of issues I know from experience affect us to some degree. The issue is also incredibly complex. Montgomery delves into the many problems and effects of what he calls dispersed cities, such as: class segregation, expensive infrastructure maintenance, obesity, violence, depression, pollution, and neighbourly distrust. All put together, the dispersed city’s residents are generally unhappy and, perhaps surprisingly, most would rather live in the dense, convivial city.

Recently Atlanta was walloped with a snowstorm that crippled highways for hours. Faced with climate change, it’s obvious that the resilient city isn’t organized around five-lane feeder highways.

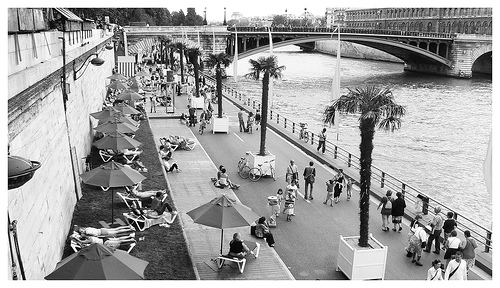

Your eyes are not deceiving you. This street is now a beach and public space. C’est Paris Plage! (Merci (e)Spry, via Flickr.)

Montgomery gives many examples of cities where action has been taken over the last few decades to reverse or prevent dispersal and to create safer, happier cities — and in the process shrink environmental impacts. Bogota‘s Ciclovia has been copied in Mexico. Portland has Mark Lakeman’s City Repair turning intersections into gathering places to build community. (His talk was excellent, by the way.) Paris, Copenhagen and New York have reclaimed road space from cars and given it back to people. Dead malls are being reimagined as mixed-use communities with gathering places, parks and public transit.

While Lakeman’s talk on reclaiming public spaces was fresh in my mind, I experienced a vision (and sound) of what could be in a convivial, happy city. For a moment, all was silent except the hum of voices. Cars had stopped at intersections, leaving about two blocks on Main St devoid of rumbling engines. Ah — can you imagine? It nearly makes me giddy.

I could probably write an essay about this book but I will instead let you discover it for yourself. I highly suggest you get a copy right away and let me know in the comments what you thought about it. Did it make you look at your city differently? Did you change any of your habits to get to know your neighbours or choose another mode of transportation?

Check out these articles in the Georgia Straight and The Guardian (latter written by Montgomery) for a little extra.